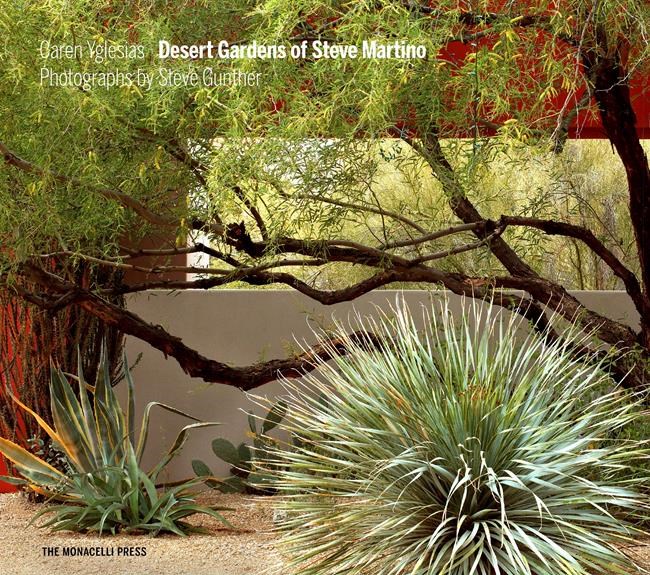

This undated photo courtesy of The Monacelli Press shows the cover of the book "Desert Gardens of Steve Martino," by Caren Yglesias. (The Monacelli Press via AP)

February 21, 2018 - 5:58 AM

PHOENIX - When I moved to Phoenix last summer, I was bewildered by all the bright green grass I saw smack in the middle of the Sonoran Desert — in residential yards, on golf courses, at community parks.

While the temperatures were hitting nearly 120 degrees, these perfect lawns sucked up huge amounts of water delivered by the shussssh-chik-chik-chik of sprinklers before the brutal orange sun rose each summer morning.

But I was drawn to the more natural-looking, drought-tolerant yards, the kind of landscaping I saw in Southern California when water rationing forced homeowners several years ago to trade their lawns for chaparral. Instead of big shade trees, there were saguaro cacti and whip-like ocotillo plants stretching their long branches into the cloudless sky. Crushed red rock took the place of Bermuda grass. Golden barrel cactus replaced rose bushes.

The newly published "Desert Gardens of Steve Martino" (The Monacelli Press, 2018) shows us how a celebrated Phoenix landscape architect uses native flora to create such natural outdoor spaces for his clients.

With a text written by fellow architect Caren Yglesias and photographs by Steve Gunther, we see how Martino creates what Yglesias characterizes as comfortable outdoor rooms. Terracotta pots, concrete benches and cantilevered stairs add character while hidden light fixtures provide nighttime drama.

Playing with geometric shapes, light and shadow, Martino's work recalls the functionalist influence of the late Mexican architect Luis Barragan. Rectangular slab walls painted in cerulean blue, burnt orange-red, cheery yellow or deep purple provide privacy.

Martino combines desert flora with steel, rocks and those colored walls to create quiet spaces where you can reflect alone or gather with others. Tapered concrete paths lead through grounds covered by crushed rock to outdoor fireplaces or water sources such as fountains or a pipe sticking out of a wall. Splashing water drowns out the roar of a nearby highway, while a wall hides a yard from hikers traversing through an adjacent wildlife area.

Arizona's state tree, the Blue Palo Verde, and Mexican fence-post cactus stand tall and straight like sentries alongside buildings. But there's no grass in Martino's projects.

"Lawn has its place in a public park, but it's ridiculous to have it at your home," Martino said, explaining his landscaping philosophy during a recent telephone interview. "Using grass at your home really is a kind of crime. Lawn mowers are not environmentally friendly."

"And we need to save our water," the 70-year-old added. "I always like to say, 'Kill your lawn, save your grandchildren.'"

Martino differentiates his projects from traditional desert landscaping, that old-fashioned mix of cacti, green-painted gravel and rusty wagon wheels that he likes to call "gardens of despair."

Instead, Martino builds habitats, with native plants attracting their symbiotic pollinators. In the book, he describes finding a vagabond plant known as a sacred datura in a bed of salvia, and being startled one evening when he saw a huge Hawk Moth suddenly fly away from the big nighttime bloom.

Martino's relationship with the desert goes back to his years as a troubled youth sent to live on a ranch, where he was charged with wrangling horses. He later served in the Marine Corps and studied art at a community college.

The landscape architect wrote in a separate introduction in the book that he found his life's calling after a college instructor suggested he visit the workshop of Paolo Soleri, an Italian architect known for his ceramic and bronze wind bells. Soleri had been a disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright when the American spent his winters at the desert home he dubbed Taliesin West.

Martino noted his dislike of Phoenix's manufactured feel, and the millions of dollars spent to make it look like it's not in the desert.

"The desert was far more interesting to me than anything man-made in the city," he wrote. "Unfortunately, the desert historically was viewed as a wasteland, where anything done to it was an improvement. The West was a resource to be exploited, and native plants were to be eradicated."

So Martino populated his landscapes with the desert's ironwood trees and Big Bend yuccas. Along with huge saguaro, he used organ pipe, silver torch, cereus and staghorn cholla cactus, as well as brittlebrush with its sunny, bright blossoms. He spilled hot pink bougainvillea and trailing lantana plants with white, yellow, and purple blooms over his trademark walls.

As he wrote in the book: "I just wanted to use desert plants in my projects, which became the idea to bring the desert into the city."

Here are a few of Martino's projects featured in the book:

___

Daniels/Falk Garden. At the Tucson property of Susan Daniels and Eugene Falk, Martino designed gardens with terraces and retaining walls over three-quarters of an acre in an effort to visually connect the property with the adjacent Coronado National Forest. He situated an infinity edge pool to extend into the desert and lead the eye toward the mountains. A runnel, or narrow channel, was created to spill water into a trough that became a drinking hole for wildlife.

___

City Grocery Garden. Interior designer Georgia Bates bought a rundown grocery store in the heart of Phoenix and transformed it into a live-in compound with garden courtyards. Martino redid the outside areas, and built a pedestrian entry and a freestanding fireplace. He left five palm trees already standing on the site, and added plants such as prickly pear cactus, creosote bush, Texas sage, and mesquite and Palo Verde trees.

___

Casa Blanca Garden. Molly and Jim Larkin called on Martino to improve on a garden outside their nearly 90-year-old adobe home in the Phoenix suburb of Paradise Valley. Martino added more cacti and trees, along with a non-traditional lap pool and a tennis court. On a lark, he also planted his first now-signature prickly pear cactus roof garden.

News from © The Associated Press, 2018